Hegemony, a concept coined by Antonio Gramsci, is a way of defining power or dominance by one group over another. Gramsci suggests that,"power is wielded in a different arena--that of culture, in the realm of everyday life--where people essentially agree to current social arrangements"(Croteau & Hoynes, 2002 p. 165-66). It is also a societal framework of the "natural order" of things or what a society thinks is normal. These "commonsense assumptions," as Gramsci puts it, are social constructions. Hegemonic constructions can be applied to a wide array of groups, whether that be race, sexual orientation, or in this case, gender.

The commercial, which (I thought) was hilariously followed by a Tampax commercial, features men driving through a jungle in attempts to escape from 'bad guys', mirroring the characteristics an action film. The commercial uses dialogue such as, "It's what guy's want" and "You can keep your romantic comedies and lady drinks, we're good." This ad purposefully singles out male and female stereotypes and pits them against each other. It's saying only "manly men" will enjoy this action film inspired commercial and only men can handle Dr. Pepper. It refuses to accept that some women like action films and some men will enjoy "lady drinks," whatever that means. It's through these types of media texts that stereotypical ideologies become normalized. "...media texts can be seen as key sites where basic norms are socially articulated. The media gives us pictures of social interaction and social institutions that, by their sheer repetition on a daily basis, can play important roles in shaping broad social definitions...the accumulation of media suggests what is 'normal' and what is 'deviant'" (Croteau & Hoynes, 2002, p. 163).

However, Croteau and Hoyes argues that "hegemony is not something that is permanent; it is neither 'done' nor unalterable...hegemony [is] a process that is always in the making" (p. 167). This is comforting, as we can be agents in changing the standard hegemonic view. Recently, the male hegemony has seen a shift in the stereotypical representation of father and mother figures in the home. Companies such as Fortune and Forbes have sung the praises of what is called "Dadvertising."

Anzaldúa, Gloria. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

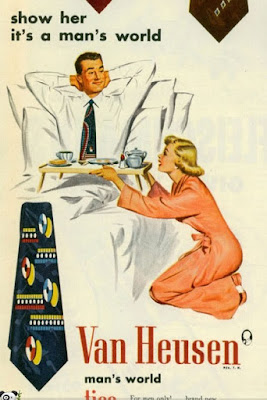

Hegemonic ideologies regarding female and male gender roles have been as diverse and fluid as they have been rigid. Hegemonic masculinity, a term first introduced by R.W. Connell, seeks to explain why men have maintained a dominant role in society. The male and female gender stereotype is structured through these perceived norms. As Patricia Sexton suggests, "male norms stress values such as courage, inner direction, certain forms of aggression, autonomy, mastery of technological skill, group solidarity, adventure, and considerable amounts of toughness in mind and body...it is only recently social scientists have sought to link this insight with hegemony"(Donaldson, 1993). The male hegemony in the past was centered around dominance of women, and in particular, women as sexual objects. Take for example, this Van Heusen print ad.

"It's a man's world." It's a world in which a man is maintaining his dominance not only verbally, but physically too; he is above her. The women in this ad also represents the female hegemony; women are submissive and may be made to be sexually objectified. Not only is she serving her man breakfast and a tie, but the position on her knees is sexually suggestive as well. The male hegemony also claims men are supposed to be masculine. Companies such as Axe or Old Spice are notorious for creating commercials featuring manly, scantily clad, men encouraging you to buy their products. Dr. Pepper went so far as to create this ad specifically for men, with the ending catchphrase, "It's not for women."

The commercial, which (I thought) was hilariously followed by a Tampax commercial, features men driving through a jungle in attempts to escape from 'bad guys', mirroring the characteristics an action film. The commercial uses dialogue such as, "It's what guy's want" and "You can keep your romantic comedies and lady drinks, we're good." This ad purposefully singles out male and female stereotypes and pits them against each other. It's saying only "manly men" will enjoy this action film inspired commercial and only men can handle Dr. Pepper. It refuses to accept that some women like action films and some men will enjoy "lady drinks," whatever that means. It's through these types of media texts that stereotypical ideologies become normalized. "...media texts can be seen as key sites where basic norms are socially articulated. The media gives us pictures of social interaction and social institutions that, by their sheer repetition on a daily basis, can play important roles in shaping broad social definitions...the accumulation of media suggests what is 'normal' and what is 'deviant'" (Croteau & Hoynes, 2002, p. 163).

However, Croteau and Hoyes argues that "hegemony is not something that is permanent; it is neither 'done' nor unalterable...hegemony [is] a process that is always in the making" (p. 167). This is comforting, as we can be agents in changing the standard hegemonic view. Recently, the male hegemony has seen a shift in the stereotypical representation of father and mother figures in the home. Companies such as Fortune and Forbes have sung the praises of what is called "Dadvertising."

"If you need evidence that a father's role in the American home has changed, look no further than television advertising. The martini-sipping head of the household, doted upon by his apron-clad wife, is long gone. Today, fathers are portrayed as cuddly caregivers, unafraid to get their hands dirty when it comes to daily parenting duties."

-Daniel Bukszpan, Fortune

The Dadvertising trend was first noticed during last year's Super Bowl ads, which is also notorious for hosting a wide array of sexist ads along with touchy-feely PSA's and those strange Dorrito's commercials. Below is an example of a Dove Men+Care ad promoting men and their roles as fathers. The commercial features various clips of fathers interacting with their children, who are all calling out "Daddy!" Advertisements depicting familial relationships often use mother-child roles, but this ad in particular chose to focus on the Dad in his own roles. These range from fathers holding infants to helping their sons with prom. Dove filmed a series of commercials to promote the idea that when a father cares, it makes him stronger.

Despite my initial criticism in that men still have to be viewed as "strong," it nonetheless offered an insight into a role that is rarely depicted in advertising, let alone revered. In fact Dove calls to attention this media oversight, saying, "Three quarters of dads say they are responsible for their child's emotional well-being, while only 20% of dads see this role reflected media. It's time to acknowledge the caring moments of fatherhood that often go overlooked." It's refreshing to see advertisement's overall ideologies adhere to today's everchanging societal standards, as too often it seems some are still stuck being "Mad Men." No longer do ads (well...some ads), as Fortune and Forbes touched on earlier, replicate the norm of the housewife as the poster child of cooking and cleaning. These "new" views are a product of our culture. It is arguably more common for men to stay at home and for women to work.

Gloria Anzaldúa touches on the idea of culture, and how these ideas were certainly not the norm, especially in her own experience. She writes, "Culture forms our beliefs. We perceive the version of reality that it communicates. Dominant paradigms, predefined concepts that exist as unquestionable, unchallengeable, are transmitted to us through the culture"(Anzaldúa, 1897. p. 38). These dominant paradigms can range from the femininity of women to the masculinity of men to white as a superior race. It is in line with hegemony in that it is the dominant force of power. It is generally accepted and readily agreed upon. Furthermore, Anzaldúa argues that, "Culture...keeps women in rigidly defined roles....deviance is condemned by the community"(Anzaldúa, 1897. p. 39-40). We've explored advertisements previously that did just that. As such, it is incredibly refreshing as well as incredibly important, to expose ourselves to ads that seek to challenge this dominance. Whether that be something as touching as "Dadvertising" or seeking to portray women in more than just sexual or caretaker roles, the crucial part is that we are challenging hegemonic norms.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

Bukszpan, Daniel. (2016, June 19). 'DADvertising': How Realistic Images of Dads Took Over TV Ads. Retrieved October 24, 2016, from http://fortune.com/2016/06/19/dadvertising-commercials-fathers-day-ads/

Donaldson, Mike. "What is Hegemonic Masculinity?"Theory and Society 22.5 (1993): 643-57. Web.